On April 26, U.S. President Joe Biden welcomed South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol to the White House for a summit meeting to celebrate the seventieth anniversary of the U.S.-South Korea alliance and open a new chapter for the next seventy years of expanded cooperation. Amid a substantial list of topics discussed by the two leaders, extended deterrence emerged as the top deliverable.

Trends and Fluctuations in the Severity of Interstate Wars

Trends and Fluctuations in the Severity of Interstate Wars

Trends and Fluctuations in the Severity of Interstate Wars

Since 1945, there have been relatively few large interstate wars, especially compared to the preceding 30 years, which included both World Wars. This pattern, sometimes called the long peace, is highly controversial. Does it represent an enduring trend caused by a genuine change in the underlying conflict-generating processes? Or is it consistent with a highly variable but otherwise stable system of conflict? Using the empirical distributions of interstate war sizes and onset times from 1823 to 2003, we parameterize stationary models of conflict generation that can distinguish trends from statistical fluctuations in the statistics of war. These models indicate that both the long peace and the period of great violence that preceded it are not statistically uncommon patterns in realistic but stationary conflict time series. This fact does not detract from the importance of the long peace or the proposed mechanisms that explain it. However, the models indicate that the postwar pattern of peace would need to endure at least another 100 to 140 years to become a statistically significant trend. This fact places an implicit upper bound on the magnitude of any change in the true likelihood of a large war after the end of the Second World War. The historical patterns of war thus seem to imply that the long peace may be substantially more fragile than proponents believe, despite recent efforts to identify mechanisms that reduce the likelihood of interstate wars.

Over the next century, should we expect the occurrence of another international conflict that kills tens of millions of people, as the Second World War did in the last century? How likely is such an event to occur, and has that likelihood decreased in the years since the Second World War? What are the underlying social and political factors that govern this probability over time?

These questions reflect a central mystery in international conflict (1–4) and in the arc of modern civilization: Are there trends in the frequency and severity of wars between nations, or more controversially, is there a trend specifically toward peace? If such a trend exists, what factors are driving it? If no such trend exists, what kind of processes governs the likelihood of these wars, and how can they be stable despite changes in so many other aspects of the modern world? Scientific progress on these questions would help quantify the true odds of a large interstate war over the next 100 years and shed new light on whether the great efforts of the 20th century to prevent another major war have been successful and whether the lack of such a conflict can be interpreted as evidence of a change in the true risk of war.

Early debates on trends in violent conflict tended to focus on the causes of wars, particularly those between nation states (5). Some researchers argued that the risk of these wars is constant and fundamentally inescapable, whereas others argued that warfare is dynamic, and its frequency, severity, and other characteristics depend on malleable social and political processes (1, 2, 6–9). More recent debates have focused on whether there has been a real trend toward peace, particularly in the postwar period that began after the Second World War (3, 10–13).

In this latter debate, the opposing claims are associated with liberalism and realism perspectives in international relations (14). The liberalism argument draws on multiple lines of empirical evidence, some spanning hundreds or even thousands of years [for example, see the works of Pinker (3) and Roser et al. (15)], to identify a broad and general decline in human violence and a specific decline in the likelihood of war, especially between the so-called great powers. Arguments supporting this perspective often focus on mechanisms that reduce the risk of war, such as the spread of democracy (16, 17), peace-time alliances (9, 18–20), economic ties, and international organizations (9, 21).

In contrast, the realism argument draws on empirical evidence, some of which also spans great lengths of time [for example, see the studies of Harrison and Wolf (22) and Cirillo and Taleb (23)], to identify an absence of discernible trends toward peace within observed conflict time series. A key claim from this perspective is that the underlying conflict-generating processes in the modern world are stationary, an idea advanced in the early 20th century by the English polymath L. F. Richardson (24, 25) in his seminal work on the statistics of war sizes and frequencies.

This debate has been difficult to resolve because the evidence is not overwhelming, war is an inherently rare event, and there are the multiple ways to formalize the notion of a trend (4, 5, 17, 26, 27). Should we focus exclusively on international conflicts, or should other types of conflict be included, such as civil wars, peace-keeping missions, or even the simple use of military force? Should we focus on conflicts between major powers or between geographically close nations, or should all nations be included? What conflict variables should we consider? How should we account for the changing number of states, which have increased by nearly an order of magnitude over the past 200 years? What about other nonstationary characteristics of conflicts, such as the increasing frequency of asymmetric or unconventional conflicts, the use of insurgency, terrorism, and radicalization, improvements in the technology of war and communication, or changes in economic development? Different answers to these questions can lead to opposite conclusions about the existence or direction of a trend in conflict (1, 2, 7, 8, 22, 23, 26–28).

Ultimately, the question of identifying trends in war is inherently statistical. Answering it depends on distinguishing a lasting change in the dynamics of some conflict variable from a temporary pattern—a fluctuation—in an otherwise stable conflict-generating process. More formally, a trend exists if there is a measurable shift in the parameters of the underlying process that produces wars, relative to a model with constant parameters. Identifying these trends is a kind of change-point detection task (29), in which one tests whether the distributions observed before and after a change point are statistically different. The ease of making these distinctions depends strongly on the natural variance of the observed data.

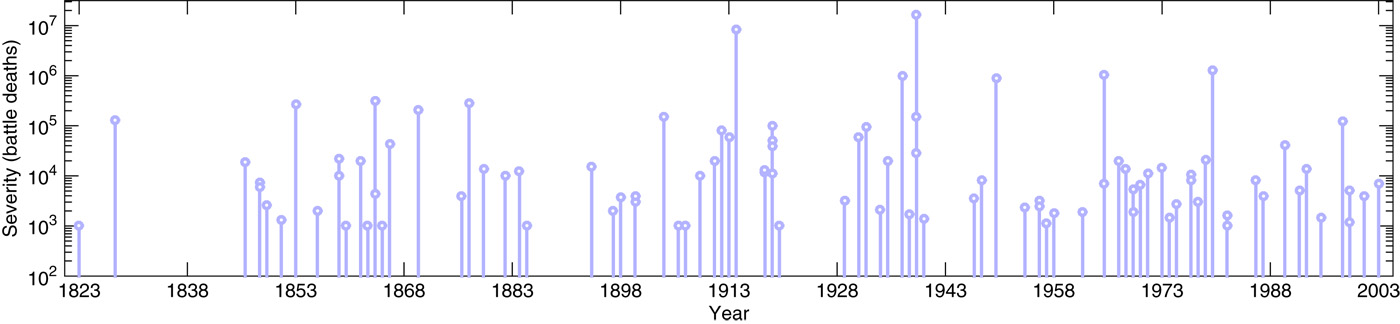

This article presents a data-driven analysis of the general evidence for trends in the sizes of and years between interstate wars worldwide and uses the resulting models to characterize the plausibility of a trend toward peace since the end of the Second World War. This analysis focuses on the 1823–2003 period and on the interstate wars in the Correlates of War interstate conflict data set (Fig. 1) (30, 31), which provides comprehensive coverage in this period, with few artifacts and relatively low measurement bias. The underlying variability in these data is captured using an ensemble approach, which then specifies a stationary process by which to distinguish trends from fluctuations in the timing of war onsets, the severity of wars, and the joint distribution of onsets and severity.

Fig. 1 The Correlates of War interstate war data (30) as a conflict time series, showing both severity (battle deaths) and onset year for the 95 conflicts in the period 1823–2003.

The so-called long peace (10)—the widely recognized pattern of few or no large wars since the end of the Second World War—is an important and widely claimed example of a trend in war. However, the analysis here demonstrates that periods like the long peace are a statistically common occurrence under the stationary model, and even periods of profound violence, like that of and between the two World Wars, are within expectations for statistical fluctuations. Hence, even if there have been genuine changes in the processes that generate wars over the past 200 years, data on the frequency and severity of wars alone are insufficient to detect those shifts. The long peace pattern would need to endure for at least another 100 to 150 years before it could plausibly be called a genuine trend. These findings place an upper bound on the magnitude of any underlying changes in the conflict-generating processes for wars, if they are to be consistent with the observed statistics. These results imply that the current peace may be substantially more fragile than proponents believe.

This article was republished from Science Advances under a Creative Commons license. It does not constitute endorsement of Analyzing War by the author. Read the original article.

Aaron Clauset, Department of Computer Science, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309, USA. BioFrontiers Institute, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80303, USA. Santa Fe Institute, Santa Fe, NM 87501, USA.

Related Articles

President Marcos Jr. Meets With President Biden—But the U.S. Position in Southeast Asia is Increasingly Shaky

Over a four-day visit to Washington, Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has been welcomed to the White House and generally feted across Washington. With President Biden, Marcos Jr. (whose father was forced out of office in part through U.S. pressure, and whose family has little love for the United States) affirmed that the two countries are facing new challenges, and Biden said that “I couldn’t think of a better partner to have than [Marcos Jr.].”

The U.S. is about to blow up a fake warship in the South China Sea—but naval rivalry with Beijing is very real and growing

As part of a joint military exercise with the Philippines, the U.S. Navy is slated to sink a mock warship on April 26, 2023, in the South China Sea.

The live-fire drill is not a response to increased tensions with China over Taiwan, both the U.S. and the Philippines have stressed. But, either way, Beijing isn’t happy – responding by holding its own staged military event involving actual warships and fighter jets deployed around Taiwan, a self-governed island that Beijing claims as its own.